Research with Body and Senses: Arts-based Research and Research-based Art (Part 2)

Kukiko NOBORI

This paper is a self-translation of an article originally published in Journal of Tokyo Zokei University 25 (issued on March 31, 2024). The author gratefully acknowledges the Editorial Committee of the Research Report of Tokyo Zokei University for granting permission to publish the English version.

本論文は東京造形大学研究報25(2024年3月31日発行)に掲載された登久希子著『身体と、感覚と向き合うアート:アート・ベースド・

(Continued from Part 1)

3. Case Studies: Mindscapes Tokyo

In this section, I introduce a project conducted within Mindscapes as a case study of ABR11. Mindscapes was an arts and culture program on mental health, carried out between 2020 and 2023 in Tokyo, Berlin, Bengaluru, and New York by the Wellcome Trust—a UK-based charitable foundation that supports global medical research. With the goal of “transforming understanding and discourse around mental health,” Mindscapes was intrinsically interwoven with both art and research. This relationship was most clearly embodied in the project of inVisible, a nonprofit organization that played a central role in many of Mindscapes Tokyo’s programs. Describing itself as a “creative place that continuously sculpts society using art as a catalyst12,” inVisible positions artistic methodologies as a core means of engaging with and addressing diverse social issues13.

The present section examines the Urban Investigation (hereafter, UI) project, undertaken by inVisible between 2022 and 2023 within the framework of Mindscapes Tokyo. While Wellcome Trust’s Cultural Partnerships division (at the time) provided the overarching framework and direction for this initiative, the specific methodologies and program designs were left to partner organizations in each city. Wellcome Trust seemed particularly interested in how its international partners and artists outside the UK would identify and address mental health-related issues through their own thematic and topical lenses. As a result, Mindscapes Tokyo came to encompass a diverse range of locally relevant themes.

3-1. About the Process

In response to a request from the Wellcome Trust to develop an art and cultural program that would investigate the city of Tokyo from the perspective of mental health, inVisible conceptualized and implemented UI as part of the broader Mindscapes initiative14. This project was designed as a collaborative inquiry into mental health, conducted jointly by artists and youth participants. The project enlisted artists specializing in food, film, and Japanese architecture to serve as “lead investigators,” each of whom worked in close partnership with a team of six to eight high school and university students—referred to as “youth investigators” (hereafter “youth”)15. The research process focused on themes such as “sleep,” “food,” and “being normal,” analyzing how these concepts intersect with mental health in urban contexts. The teams aimed to articulate their findings through the creation of tangible outputs, which served both as representations of their research and as vehicles for public engagement.

Originally, the Wellcome Trust envisioned the final output of the UI to be a film work, one that would highlight a specific facet of mental health as situated in each participating city. In other Mindscapes locations, the resulting works often took the form of film-based productions, including those derived from interviews16. However, for inVisible’s curatorial and operational team, the directive to produce a film as the predetermined endpoint of the research posed a conceptual dissonance. It was perceived as an externally imposed framework that risked undermining the exploratory and processual nature of the investigation. In response, inVisible proposed an alternative format: a collaborative research project between artists and youth culminating in a semi-open exhibition modeled after an open studio format, with the research process itself documented on film. This counter-proposal underscores inVisible’s commitment to a mode of inquiry that privileges process over product, and reflects a broader critique of outcome-oriented research paradigms in favor of more emergent and participatory forms of knowledge production. The proposal submitted by inVisible was received with interest by the Wellcome Trust, and given that the project would ultimately include the production of a film work in some form, the foundation raised no objections. Thus, the project was set in motion. Due to space limitations, this paper will first provide an overview of the project’s general trajectory before offering a partial reflection on the notion of uncertainty within ABR17.

The UI project identified as central issues of mental health those related to “loneliness and stress” within the urban environment, as well as the difficulty individuals face in discussing their mental state18. The planning and organizing team at inVisible was particularly concerned about the lack of intergenerational dialogue on these issues and the absence of spaces where young people’s voices could be heard—concerns that raised fundamental questions about the conditions necessary for listening and mutual engagement. With this awareness as a starting point, inVisible assembled four teams: three research groups led by artists specializing in food, architecture, and film, respectively, and one documentation team tasked with filming the research process itself. Youth investigators included high school students, recruited through open calls at their school, and university student interns19. Notably, the decision to position the documentation effort as an integral part of the collaborative research framework reflects a distinctly ABR-oriented perspective, one that seeks to explore the reflexive potential of documentation itself.

The lead investigators were not specialists in fields conventionally associated with mental health, such as medicine, welfare, or education. Rather, their expertise lay in shaping ideas and concepts through their respective media—culinary practice, architecture, and filmmaking. Underlying this “non-expert-driven” research model was a concern that the topic of mental health is often perceived as either too complex or too distant—a matter best left to others, so-called “specialists”. The UI project sought to challenge this perception by emphasizing “amateur” or non-specialist engagement rooted in lived experience. In this sense, both lead investigators and the youth occupied a shared position as non-experts throughout the research process of developing concepts and ideas collaboratively.

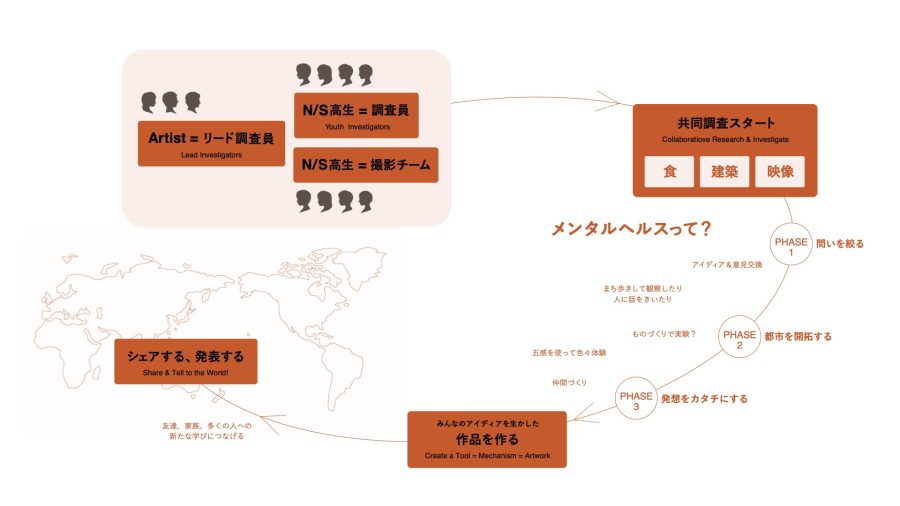

Each lead investigator proposed a broad thematic focus: the food team sought “a place to engage with one’s mind,” the architecture team explored the idea of “creating the ultimate sleeping space,” and the film team pursued the expansive theme of “being normal (futsū, ふつう, “normal” ).” However, the concrete direction of each project was collaboratively shaped through ongoing research and dialogue between lead investigators and the youth. As outlined in the “Process Map” below, the research unfolded across four distinct phases.

A Process Map of the Urban Investigation Developed by NPO inVisible ©︎NPO inVisible

Throughout each phase of the project, the research and inquiry processes were designed to be fundamentally collaborative. While lead investigators occasionally offered hints or support as needed, the emphasis was placed on ensuring that the research unfolded through shared engagement. The collaborative process itself was valued more highly than any final output. This raises the question: what does it mean to foreground process? In what follows, we consider how uncertainty—understood as a potential catalyst for change or the emergence of the new—was positioned within the collaborative research framework. Notably, the lead investigators were not educators or facilitators who typically work with high school or university students. As such, the nature of collaboration remained largely undefined not only for the youth but also for the lead investigators themselves. Yoyo.,the lead investigator of the food team, reflected on the uncertainty and openness of the collaborative process as follows:

“In a way, I relied on others—I had some intentions, but rather than doing everything myself, I consciously stepped back. Since this wasn’t going to be a work of my own alone, but something created together with high school students, I tried not to perfect things on my own. I made sure to leave room for possibilities—like, ‘What should we do?’—and I was okay with things not being fully decided. If someone noticed that something was missing and took the initiative to fill in the gap, that would be great. But even if that didn’t happen, that was fine too. I approached it with that kind of attitude—believing that things would somehow work out. And in a way, I trusted in that20.”

This account illustrates how uncertainty was not merely tolerated, but rather embraced as a space for co-creation—one in which openness, trust, and the suspension of control became central strategies in enabling new ideas and relationships to emerge. In this sense, the process was not a linear execution of a pre-defined plan, but an unfolding inquiry shaped by the dynamics of collaboration itself.

A performance scene from Miso Shiru Temae at Mindscapes Tokyo Week. ©︎NPO inVisible

Over the course of approximately three months of research, each team developed and refined their ideas through hands-on activities and critical dialogue. The food team, for instance, engaged in actual cooking sessions, and visited markets, held workshops, and exhibitions. The architecture team conducted site visits to bedding manufacturers, disaster preparedness facilities, and architectural exhibitions. Meanwhile, the film team watched various film works and undertook experimental filming exercises. Throughout these experiences, members of each team shared questions, impressions, and reflections, gradually shaping the conceptual direction of their projects.

The food team identified the lack of time to engage with oneself in contemporary urban life. In response, they developed the concept of Miso-shiru Temae (literally, “the ritual before miso soup”), as a means of fostering moments of mindful self-encounter to support mental well-being. The idea emerged from the youth members’ shared perception that “drinking miso soup has a calming effect,” which was brought into dialogue with the lead investigator’s interest in the formalized rituals of tea ceremony (temae, 手前, tea serving, procedure). Through a process of trial and error, the team devised a method for creating time and space in which individuals could reflect on their own mental states while preparing and eating miso soup.

The architecture team concluded that it was not possible to define a singular “ultimate sleeping space (究極の寝床),” as the ideal environment for sleep varies greatly depending on the individual and their specific circumstances. Based on this insight, the team produced a range of outputs: individual visions of the “ultimate sleeping space” were compiled into both a VR experience and a printed booklet. Additionally, the team constructed a full-scale physical bed using traditional Japanese architectural techniques and developed an interactive element that invited participants to vote on their preferred scents for optimal sleep, resulting in a multifaceted set of outcomes21.

First meeting between lead researcher Takatsune Hayashi and youth researchers at ‘Tokyo Garage,’ discussing what is needed for sleep. Photo: Masanobu Nishino.

3-2. To Embody the Film

Senzo Ueno, the lead investigator of the film team, had long harbored doubts about binary classifications such as “normal/abnormal” and “sick/healthy,” stemming from a personal experience with his close friend. He shared this question with the youth, and much of the research period was devoted to sustained dialogue and discussion among the team members. One of the youth members remarked, “From the very first session, it felt like we spent a lot of time showing our true selves,” highlighting the depth and intimacy of the conversations that unfolded. Over time, a shared sentiment began to emerge among the youth: despite the many words they had exchanged, they wanted to create something that did not rely on verbal explanation22.

The final work, which was based on conversations with “important people” in their lives—such as friends, classmates, and mentors—about the question of “what is normal,” was thus filled with words, yet aspired to go beyond them. The question then became how to exhibit such a work. The method they chose allowed the viewer to feel the embodied experience of both filming and being filmed, as well as the interpersonal relationship between the two participants. The exhibition setup featured CRT monitors that reflected the viewer’s own image on the screen when the room darkened. In the dimly lit gallery space, the brightness of the screen or the appearance of the end credits caused the viewer’s own reflection to appear in the monitor. This intervention interrupted the possibility of viewing the work as a detached third party and instead compelled viewers to reflect—consciously or unconsciously—on how they themselves might relate to what they were witnessing. Furthermore, the decision to place the viewing chairs “close enough to reach out and touch the monitor” was a deliberate choice meant to allow viewers to physically sense the proximity at which the actual filming had taken place23. During the shoot, each youth member faced their “important person” directly, holding hands while placing the camera between them.

In this sense, the work produced by the film team can be understood, in Bishop’s terms (2023), as “embodied and durational”—a materialization and extension of their research through affective and bodily engagement. Moreover, the curatorial strategies employed in the exhibition further enhanced the physical and corporeal mode of viewing, contributing significantly to what Bishop calls “a bodily, embodied mode of spectatorship.”

An installation by the film team at Mindscapes Tokyo Week. Photo: Masanobu Nishino.

This embodied and sensory approach was not limited to the film team’s exhibition alone. In the food team’s installation, visitors were invited to consume miso soup and a small rice ball as part of a ritualized “temae” experience. In the architecture team’s exhibition, participants could compare various scents deemed optimal for sleep or physically lie down on one of the “ultimate sleeping space” that had been constructed. Each team devised methods that encouraged visitors to engage their own bodies in action, appealed to a variety of senses—including taste and smell—or, at the very least, prompted imaginative engagement with those senses even in the absence of direct physical participation24. Through these curatorial strategies, the exhibition created opportunities for visitors to frame mental health not as an abstract or distant issue, but as something that could be felt and considered personally.

More importantly, the UI project was sustained by a process in which the investigators—who did not consider themselves mental health experts—reflected on and reinterpreted mental health concerns in ways that resonated with their own lives. Although it is said that one in four people worldwide experience some form of mental distress each year25, thinking about mental health as something that concerns oneself is not necessarily an easy task for many. This gap in personal engagement often leads to ignorance and indifference, which in turn can foster stigma and prejudice.

The Urban Investigation functioned as a platform for encouraging interest in and reflection on mental health by grounding the inquiry in everyday, relatable themes. By foregrounding embodied experience, affective imagination, and collaborative exploration, the project invited both participants and audiences to encounter mental health not as a specialized medical discourse, but as a deeply human and shared concern.

4. Conclusion

The UI project conducted as part of Mindscapes Tokyo was a collaborative research initiative in which artists worked together with high school and university students to explore mental health through themes such as “sleep,” “food,” and “being ordinary.”

Conceivably, Mindscapes could have taken a more systematic and expert-driven approach to addressing mental health issues in a city like Tokyo—re-examining them through professional perspectives, utilizing data from surveys, interviews, and statistical analyses, and presenting the results in an “outreach”-oriented format to the general public. However, the fact that Mindscapes was conceived by the Wellcome Trust as an arts and culture project suggests a different intention: to address goals that conventional forms of outreach or scientific research alone cannot reach26—to help shift the ways in which we understand and speak about mental health. Throughout the Mindscapes program, the Wellcome Trust left considerable “space” for interpretation and response. This openness, as discussed in Section 3-1, allowed the inVisible team to reinterpret the role of film within the UI project and to propose an alternative framework. This structural openness mirrors what the lead researcher yoyo. described as “leaving room” in the collaborative process, and in both cases, uncertainty became the impetus for generating new directions. Such emergence of new directions may also be understood as the exercise of “creativity.”

If viewers of the UI films, participants in the Miso Soup Ritual (Misoshiru Temae), or those who physically experienced the “Ultimate Sleeping Space” exhibitions found themselves reflecting more deeply on mental health, it is likely because these ABR practices succeeded in fostering what Bishop (2023) refers to as “digested, lived, and sensuous encounters.” In ABR, the perspective that enables individuals to relate to a problem as “one’s own” emerges from the spaces of openness embedded in both the process and the outcomes. From these spaces, new and unforeseen creative developments may yet arise.

Acknowledgment

This article is part of the research outcomes supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 22J40018). I would like to express my gratitude to Ms. Hiroko Kikuchi, Mr. Akio Hayashi, Ms. Mami Arao, and all the members of inVisible, and Danielle Olsen from Wellcome Trust for their generous support during my research. (The institutional affiliations of the individuals acknowledged here are as of the time of the original publication.)

References

Bishop, C. (2023) “Information Overload: Claire Bishop on the superabundance of research-based art,” Artforum, April 2023 https://www.artforum.com/print/202304/claire-bishop-on-the-superabundance-of-research-based-art-90274(Accessed on 2023/9/15)

Csordas, T. S. (1994) Introduction: the body as representation and being-in-the-world. T. S. Csordas (ed.) Embodiment and Experience: The existential ground of culture and self. 1-24, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Daniels, I. (2019) What are Exhibitions For?: An Anthropological Approach. London: Bloomsbury.

Foster, H. (1995) The Artist as Ethnographer? G. E. Marcus and F. R. Myers (eds.) The Traffic in Culture. 302-309, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Howes, D. (2011) The Senses: Polysensoriality, F. E. Mascia-Lees (ed.) A Companion to the Anthropology of the Body and Embodiment. 435-450, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ishii, M., Iwaya, A., Kanatani, M., & Kasai, E. (2022). Introduction. In M. Ishii, A. Iwaya, M. Kanatani, & E. Kasai (Eds.), Anthropology of the Senses. 1–16, Kyoto: Nakanishiya Shuppan. (in Japanese)

Ito, R. (2018). Art-Based Research and Its Potential. Nanzan Junior College Journal, 39, 203–213. (in Japanese)

Kara, H. (2020) Creative Research Methods: A Practical Guide, Second Edition. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Marcus, G. E. and Clifford, J. (eds.) (1986) Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkley: University of California Press.

Miyasaka, K. (2019). A Note on the Significant Trend of the Recent Advancement in Sensory Anthropology. Journal of Tokyo Online University, 2, 169–185. (in Japanese)

Moon, K. (2023) “Research Art is Everywhere. But Some Artists Do It Better Than Others”. Art in America. https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/what-is- artistic-research-1234660125/ (Accessed on 2023/9/15)

Niwa, T. and Yanai, T. (2017) Flowers’ Life: Notes and Reflections on an Art-Anthropology Exhibition. 75-87. Arndt Schneider (ed.) Alternative Art and Anthropology: Global Encounters. London: Bloomsbury.

Okahara, M., Takayama, M., Sawada, M., & Tsuchiya, D. (2016). Arts-based research : a movement for sociological activities. Mita Journal of Sociology, 21, 65–79, Mita Sociological Association (in Japanese)

Okahara, M. (2017). Arts-based research : Nachspielend/Erleichternd/Performance. Journal of Law, Politics and Sociology, 90(1), 119–147. The Association for the Study of Law and Politics, Keio University (in Japanese)

Pink, S. (2015) Doing Sensory Ethnography, 2nd edition. London: SAGE.

Schneider, A. and Wright, C. (2006) The Challenge of Practice. Schneider and Wright (eds.) Contemporary Art and Anthropology. 1-28. Oxford: Berg.

Steyerl, H. (2010) “Aesthetics of Resistance?: Artistic Research as Discipline and Conflict. Traversal Texts art/knowledge: overlaps and neighboring zones”. https://transversal.at/transversal/0311/steyerl/en (Accessed on 2023/9/15)

Endnotes

12 From the website of the NPO inVisible: https://www.invisible.tokyo/about (accessed on September 15, 2023)

13 InVisible has carried out projects that address social issues through artistic methods in various regions across Japan, including Tokyo and Fukushima.

14 From the website of the NPO inVisible: https://www.invisible.tokyo/mindscapestokyo (Accessed September 15, 2023)

15 This was the name commonly used by members of inVisible in their daily activities within Mindscapes Tokyo.

16 For example, the video work Mindscapes: Berlin Conversations on Mental Health, produced in Berlin during this period, is also available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WjT7_kE1czU (accessed on September 15, 2023).

17 The website produced by InVisible includes not only information on the Urban Investigation but also detailed documentation of the various projects carried out as part of Mindscapes Tokyo. As one example of utilizing such records, this paper specifically refers to the “production notes” created by youth researchers, as well as an interview video with the lead researcher conducted by the documentation team. Additionally, there is a separate website created by a group of youth researchers involved in the Urban Investigation as part of the activity report and exchange event Mindscapes Tokyo Week (February 20–28, 2023): https://mindscapestokyoweek.wixsite.com/my-site (accessed on September 15, 2023).

18 From the website of the NPO inVisible: https://www.invisible.tokyo/mindscapestokyo (accessed on 2023/09/15)

19 In collaboration with the Experiential Learning Division and the Experiential Learning Planning Section of N High School and S High School, operated by the KADOKAWA Dwango Educational Institute, students were recruited through an open call. As a result, the participating students initially perceived the project as a form of “extracurricular activity.” In addition, university and high school students who were interning at InVisible also joined the project.

20 From the interview with lead researcher “yoyo.” Filming and editing by Masanobu Nishino (artist, video director), Date of filming: February 20, 2023 https://www.invisible.tokyo/mindscapestokyo (accessed on September 15, 2023)

21 The exhibition was held during Mindscapes Tokyo Week from February 20 to 28, 2023 (at YAU STUDIO). The production notes and outcomes of each team are also available online.

22 From Tama-chan’s “Production Notes: Film × Mental Health” and “Notes on the Zoom Meeting on October 28” https://invisibletokyo.notion.site/d42647005f864fefa56d7677f259639f (accessed September 15, 2023)

23 From Tama-chan’s “Production Notes: Film × Mental Health” https://invisibletokyo.notion.site/d42647005f864fefa56d7677f259639f (accessed September 15, 2023)

24 The exhibitions by each team were showcased at the Mindscapes Tokyo Week (February 20–28, 2023, at YAU STUDIO). Rather than presenting the completed works, the aim was to create a dynamic exhibition resembling an “open studio.”

25 From the Mindscapes Tokyo website: https://www.invisible.tokyo/mindscapestokyo (accessed September 15, 2023)

26 From the Wellcome Trust’s Mindscapes website: https://wellcome.org/what-we-do/our-work/mindscapes (accessed September 15, 2023)