ウェルカムビルディングの外観 ©️Wellcome Collection

医療とアート

Medicine and Art

ウェルカムトラストが「芸術」や「文化」を医療の分野に取り入れ始めたのはいつ頃からですか?

When did Wellcome start implementing art and culture to the field of medicine?

ウェルカム・トラストの誰に尋ねるかで変わってきますね。みんな違ったストーリーを教えてくれると思います。わたしは、ウェルカム・トラストをつくったヘンリー・ウェルカム(1853-1936)に遡ると思っています。彼は数百万点のものからなるコレクションをつくりました。ルーヴルの5倍とも言われます。死後、彼はこのコレクションを人間と動物の健康改善のために遺しました。そもそも、彼は医学についてというよりも健康について関心があったので、それに関連するものが蒐集されました。例えばシェルターなども、身体を守るものという観点から蒐集されました。武器もコレクションに含まれています。ウェルカムはそれも身体を守るためのものと考えたからです。

Depending upon whom you talk to within the Wellcome Trust, people have different stories to tell. Henry Wellcome (1853-1936) built up a collection of more than a million objects, which is said to have been about 5 times the size of the Louvre. He set up the Wellcome Trust. When he died, he left his wealth and his collection “for the betterment of animal and human health”. He talked about health more than medicine, so he included in his collection, for example, shelters. Shelter is something to protect your body. Weapons are also in the collection, because he thought it was also something to protect your body.

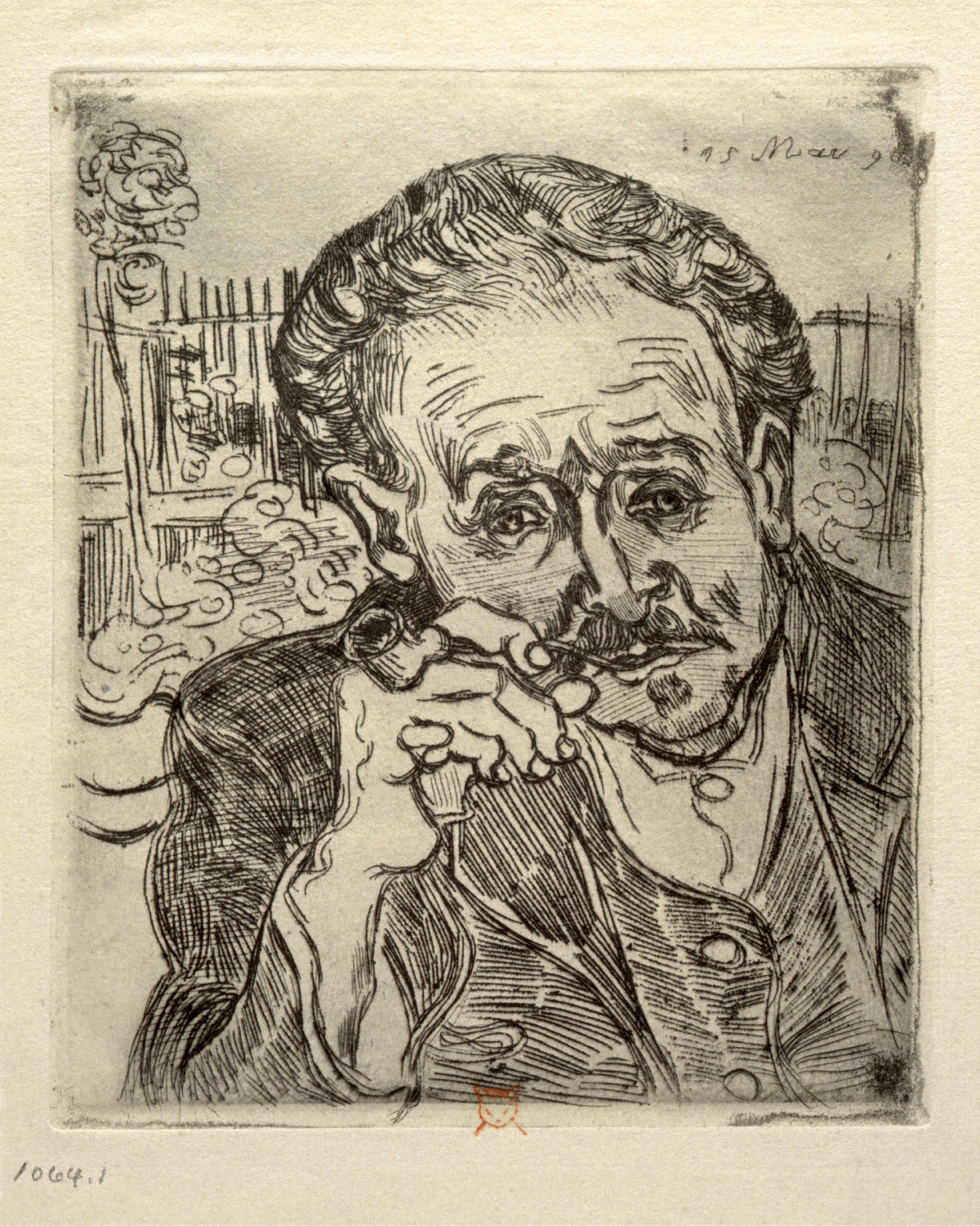

ヘンリー・ウェルカムは、美的な意味でアートに興味を持っていた訳ではありませんでした。彼は、しるしをつけること(mark-making)に興味がありました。[例えば]コレクションのなかには、同じ視覚的なものを描いた異なるものが収められていたりもします。彼は技術の歴史にも興味がありました。コレクションのなかには、医者を描いたゴッホの美しいエッチングもあります。でもゴッホの美しいエッチングだから蒐集されたというよりは、医者を描いたものだから蒐集されたのです。ヘンリーのモチベーションは、芸術によるものではなかったのです。わたしの経験から言うと、[ウェルカム・トラストにおける]芸術文化[と医療分野]との関係は、世界中から集められた物質文化のコレクションに端を発していると思います。

He was not especially interested in art in an aesthetic sense. He was interested in mark-making. Within the collection, there were some items which depicted the same visual things. He was interested in the history of technology, as well. In his collection, there is a beautiful etching of a doctor by Van Gogh. It’s not in the collection because of the beauty of the etching, but because it is about the doctor. His motive was not about art. I would say, from my experience, the relationship with art and culture stems from this collection of material culture that comes from around the world.

精神科医のガシェを描いたゴッホのエッチング

Paul Ferdinand Gachet. Etching by V. van Gogh, 1890. Wellcome Collection. Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

今のウェルカム・コレクションは、ライブラリーとミュージアムから成り立っていますが、初めはライブラリーだけでした。このコレクションの芸術的な側面を取り上げるような公的機関は初めは存在しなかったということですね。未だ誰もこのコレクションの全容を理解できません。それを理解しようと努めているところです。

The Wellcome Collection consists of a library and a museum. The beginning was a library. There was no public institution for the interpretation of the artistic side of this collection. No one still completely understands this collection. People are still trying to understand it now.

ウェルカムコレクションにあるリーディングルーム。一般に開放されている。©️Wellcome Collection

ウェルカムでのあなたの仕事について聞かせてもらえますか?

Could you tell me a little bit more about your work in Wellcome Trust?

2007年にウェルカム・コレクションが設立される前に、ケン・アーノルドと一緒に大英博物館で「Medicine Man」(2003)という展覧会を企画しました。100万点以上の可能性をもった所蔵品とともに仕事するなかで、それら全てを知る「専門家」になることは不可能だと実感しました。自分の無知を認め、自分自身の好奇心や直感に従い、コレクションに関係する異なった分野の専門家を探して、協働したり話を聞いたりする必要がありました。わたしは、知っていることが最もわずかで、でもいつも意味のあるつながりをつくることに興味を持っているという立場にあることがほとんどです。

Before the Wellcome Collection was set up, I curated a show called “Medicine Man” with Ken Arnold in 2003 at the British Museum. Working with the possibility of more than a million objects I realized it was impossible to know about them all, to be an ‘expert’. I needed to admit my ignorance, follow my curiosity and intuition and find the experts about parts of the collection to collaborate with and listen to. I’m often the person that knows least but always interested in making meaningful connections.

「Medicine Man」の以前には、ケン・アーノルドとわたしでアーティストと科学者のコラボレーションを促進するプロジェクトも行なっていました(1996-2006)。「Sciart」というイニシアチブで、アーティストと科学者の協働に助成金を出すというものでした。そのプロジェクトは10年ほど続き、その後、常設のウェルカム・コレクションができたのです。歴史的なコレクションは重要です。どのように視点や考え方が変わってきたのかを常に私たちに思い出させてくれます。コレクションの共通するテーマは、医学というよりも健康についてであり、また医学が何を含み、何を含まないかという見方の変化についてです。コレクションは、国際的な視点を常に思い出させてもくれます。「Medicine Man」の準備をしていたとき、倉庫で何時間も過ごしました。このコレクションに関連してアーティストや作家を呼んでくることは面白いと思います。アート的な問いは、時に異なった問いをひらくことができます。

Before Medicine Man, I also worked with Ken Arnold, for a project called Sciart. This was an initiative to bring artists and scientists together, working in collaboration. We set out deliberately to try to encourage artists and scientists to work together. That happened for about 10 years. And after that, there was an opening up of our collection which made more permanent sharing possible. I think this historical collection is important. It’s a reminder of how ideas have changed. The common theme was health rather than medicine and the changing ideas of what medicine includes and doesn’t include. The collection is a constant reminder of an international perspective. I spent a lot of time working in store rooms when I was preparing Medicine Man. I think it’s interesting to bring artists and writers into a relationship with the collection. Sometimes artistic questions can open up different sets of questions.

ウェルカムコレクションの常設展「Being Human」は、21世紀において「人」であることはどういうことかを遺伝学や感染症、環境破壊、心と身体といった側面から問う展示。©️Wellcome Collection

物事を別の方法でみる

To Look at Things Differently

個人的には、芸術や文化というのは、予期しないことや驚き、物事の異なる見方をもたらす強力な方法だと思っています。ウェルカムの国際文化プログラムの前史として、私がインディペンデント・キュレーターとして関わったインターナショナル・レジデンスの設立があります。ウェルカム・トラストはベトナムとタイ、マラウィ、ケニヤ、南アフリカとイギリスのサンガー研究所での研究に[当時]資金提供をしていました。「Art in Global Health」(2012-2013)というプロジェクトは、それらの医学研究所にアーティスト・イン・レジデンスをつくったらどうか、というアイデアから誕生しました。とくにそのとき気づいたのが、協働で仕事をする際には他の人の言うことに耳を傾けなければならないということでした。そうでなければ、自分が何を知っていると言うのでしょうか。リサーチ・ベースのアーティストと仕事するときも、耳を傾けなければいけません。彼らと興味が重なるところを見つけて、こうした答えを見つけるためにです。芸術や文化がそこで何ができるのか、どのような対話を通して、芸術と科学が、非常に異なった視点のためのスペースをひらくことができるのかを見いだすために。

Personally I think art and culture are very powerful ways of opening up unexpected outcomes or surprises or a chance to look at things differently. As a kind of history of our international cultural programs, I worked – as an independent curator – to set up a programme of international residencies called “Art in Global Health”. The residencies were developed in collaboration with Wellcome funded research centres in Vietnam, Thailand and Malawi, Kenya and South Africa and at the Sanger Institute in the UK. The idea of the residency program started from the question “What would it look like if you set up artist in residencies in medical research centers?” And that experience confirmed my belief that you really have to listen to other people when you work in collaboration. Otherwise, what do I know? Same as when you work with research-based artists. You discover an overlapping interest and figure out what art and culture can do, what kind of conversations art and science can allow to open up spaces for very different perspectives.

「Art in Global Health」はそれぞれの都市における滞在制作で、ウェルカム・コレクションではそれに基づいて「Foreign Bodies and Common Ground」(2013)という成果展も行いました。カタログでは、芸術作品や芸術実践と科学的なリサーチ・コミュニティの仕事をどのように関係づけるのかを考えました。そこで、見開きの片側1ページにはアーティストの行なったことの説明、そしてもう片方のページには、その実験の科学者を招いて作品について応えてもらうことにしました。それらの二つの世界はときに切り離されているものです。でも、例えばこうした話もあります。ベトナムでレジデンスを行なったレナ・ブイは、人間と動物の健康の関係における人獣共通感染症に関心をもっていました。そこで彼女は羽毛の工場でしばらく過ごしたのです。SARSが流行していた時期だった為、感染症と関連づけられることで、その地方のコミュニティは経済的に大きな打撃を受けていました。そのコミュニティ自体では病気が出ていないにもかかわらず、鳥の羽を扱っているからという理由で、経済的な妨害にあっていたのです。レナはコミュニティで多くの時間を過ごし、美しい映像作品をつくりました。それについて科学者は「リサーチャーとしてそのコミュニティに入ることはできない。タブーがあるから。病気について調べるためにやって来たと言ったら、誰も私と話したがらないでしょう。だから行くことはできないのです」と書いています。アーティストは、科学者が行けないような場所にも、人々と話をするためにコミュニティに入っていくことができます。このことは彼に[科学的なリサーチに]もっと人文科学、人間性を取り込むことの重要性を気づかせたと言います。

Art in Global Health was a residency in each city. It also became an exhibition at Wellcome Collection. It was called “Foreign Bodies, Common Ground”. In the catalogue, I thought “How do we build a relationship between artistic works and practices and the work of the scientific research community?” So, you see there are 2 pages. One is the descriptions of what artists did and on the other page, I invited scientists of the research to respond to the artwork. Sometimes those two worlds work quite separately. But, for example, Lêna Bùi, who was the artist in resident in Vietnam. She was interested in zoonosis – the relationship between human and animal health. She spent some time in the feather farms in a rural community. It was the time of SARS, so this community suffered a lot of economic impacts from being associated with this disease, even though they didn’t have it themselves. Because they were working with bird feathers, there were economic blocks to their work. Lêna spent a lot of time in the community and she made this beautiful film. The scientist who wrote about it said “This is really interesting for us because as a researcher I can’t go to this community because of the taboo around it. When I come to study disease, people don’t want to talk to me, so I cannot come”. She said artists could go to have conversations where researchers couldn’t. It made her realize the importance of bringing in more humanities.

Where birds dance their last (still), 2012. By Lêna Bùi

Courtesy of the artist and Wellcome Collection

わかります。よく似た話を人類学者から聞いたことがあります。ある人類学者が、いつも自分が調査しているポーランドの小さなコミュニティにアーティストと一緒に入ってアートプロジェクトを行ったときに、そのコミュニティの人たちが、これまで聞いたことのない話をたくさんしてくれたそうです。

I understand. I heard a very similar story from an anthropologist who went to a small community in Poland with an artist and found out that in an art project, the people in the community talked to him a lot and he could hear many different stories he had never heard before.

そう、[ほかの手段では]できないことを芸術と一緒だとできるのです。普段できないような会話であるとか。[それは芸術がもつ]ひらかれて探検的な何かです。あらゆるアーティストという訳ではなくて、リサーチに関心があったり、リサーチベースの芸術実践を行う、相応しいアーティストと一緒に仕事をすればですね。そもそも知識とは何なのか。私たちは何を集めて分かち合うことができるのか。このような話題にも、ティム・インゴルドの議論が当てはまりそうですね。場所の特殊性、現実の人間との現実的な関係性を通してニュアンスや感情や感覚、そして政治を理解するということについて。

Yes, you can do with art things you can’t normally do. Have conversations that you can’t usually have. Because of something open and exploratory. If you’re working with the right artists, not all artists, but those who have a research interest and do research-based art practices. And then what knowledge is at the other end? What is knowledge and what can we collect and share? Something about Tim Ingold’s work seems relevant to this conversation as well, about specificity of place and real relationships with real people and understanding nuance and emotion, feelings and politics.

そうですね、インゴルドの議論は今日のアート実践をよく説明していると思います。

Yes, Ingold’s arguments explain a lot about today’s art practices, I think.

芸術やアーティストが調査先のコミュニテイで果たす役割は興味深いものです。彼らは知識のヒエラルキーみたいなものを崩すことができるのだと思います。もちろん学問的な専門性は重要です。でも[アーティストのような]ある人たちとはたらくことで可能性が拡がったり開かれたりするあり方は、単独では予想しなかったような気づきをもたらし、新しい協働のあり方をも実現してくれると思います。

It’s interesting in terms of the role of art or artists. What kind of role can they play in being the center of communities of fellow enquirers? They’re help to collapse something like a hierarchy of knowledge as well, I think. I do believe in disciplines and specialism, but I think there’s something about this expansiveness and openness of working with particulars. You can reach unexpected insights and open up collaborative ways of working.

想像的な見方の役割ってどのようなものでしょうか? それはとても個人的な見方です。個人的で、想像的で、でもそれは政治的でもあります。[Mindscapesに参加しているアーティストの]カダ・アティアも、想像や感情の領域について話しています。人々が集まって、一般的なシステムの外で語ることができるような場所や空間はどこにあるのでしょうか? より広がりのある集団的な空間を実現する場所として、図書館とか公園とか、ミュージアムなどが思い当たりました。

What is the role of imaginative perspectives? They are very personal perspectives. They are personal and imaginative and political. Actually Kader Attia [who participates to Mindscapes] speaks about this field of the imaginative and emotional. Where are the places or spaces where people can come together to talk with each other outside of normal systems? That’s how I think about libraries or parks or museum collections or gallery spaces that allow more expansive collective spaces..

そこは、安全、少なくともより安全でなければならないですね。

And it has to be safe, or safer.

そうですね、ときに安全でない対話をもつための安全な場所でなければならないですね。あるいは、ある意見に同意しないでももちろん大丈夫な場所。気持ちよく異議を唱えられる場所ですね。メッセージを伝えるというよりも、さまざまな考え方にあふれた場所です。

Yes, a safe place to sometimes have unsafe conversations as well. Or disagree, you can disagree, of course, agreeably. That’s a place for multiplicities of ideas rather than directing or delivering messages.

インターナショナル・プログラムについて

On International Programs

ウェルカムはたくさんのプログラムをイギリスの外でも行なってきました。インターナショナル・プログラムについて、どのように開催都市を選んでいるのですか?

Wellcome Trust has been running many programs outside of UK. What is the criteria of choosing cities for international programs?

「Art in Global Health」の場合は、ウェルカム・トラストが資金援助している医療関連の研究センターが既に持っていたネットワークに基づいて選ばれました。「Contagious Cities」の場合は、まずウェルカムの内部で検討を重ねました。ニューヨークとジュネーブ、香港という案が出てきてから、「この3都市に相応しいどんなプログラムを企画できますか」と私に話がきました。ジュネーブにはWHOの他にも国際的な保健関連の団体があります。ニューヨーク州は文化と科学のハブであり、意識的に国際都市であろうとしています。香港も同様でした。ウェルカムには影響力のある投資チームがあり、彼らは金融におけるハブとしての香港に数多くの国際的なコネクションを持っています。

Art in Global Health was based upon an already existing network of medical research centers where Wellcome was the significant funder, so Wellcome already had a relationship in those places. With Contagious Cities, there had been some internal conversations about where in the world Wellcome would do cultural international programs. The cities they landed on were New York, Geneva, Hong Kong. Then they said to me “What could you create relevant to those three places?” Geneva is a significant international place. The World Health Organization as well as global health organizations are there. New York State is quite a hub of science and culture and self-consciously very international. Hong Kong was similar at that point. Wellcome has a significant investment team and this investment team has a number of international connections in Hong Kong as a financial hub.

私へのお題は、それらの都市の公衆とステークホルダーに向けて、ウェルカムトラストは何ができるのかというものでした。さらに[ウェルカムの]オフィスが設立されたばかりのベルリンも加えられました。おそらくブレグジットとの関係で、ヨーロッパとの関係性を保ち、私たちは国際的な対話や協力といった価値を信じているということを[ウェルカムは]示したかったのだと思います。

The brief for me was what could Wellcome do that would be both public facing and stakeholder facing in these cities. Later they chose to set up an office in Berlin. I believe that some of the reason stems from Brexit. The idea was that it was good to have a European presence of some sort, to be pro-Europe, pro-international and to show that we believe in the value of international dialogue and cooperation.

Covid-19のパンデミックの2年前にContagious Citiesを企画しました。どのようにそのアイデアが生まれましたか?

It was 2 years before the Covid-19 pandemic that you organized Contagious Cities. How did this idea emerge?

「Contagious Cities」のアイデアが生まれた理由は、わたし自身のバックグラウンドが科学史と科学哲学で、検疫(quarantine)そのものや検疫の歴史にもずっと興味をもっていたからです。検疫に関する展覧会について長らく考えていました。それは時代を超えて古代からあり、本当の意味でグローバルな現象です。世界中のどこにでも検疫に関わる何らかの経験があります。そして、それはとても詩的で、40日という意味のラテン語(quarantina giorni)に由来します。詩的であり、時代を超えて全世界的ということで面白い主題です。なので[ウェルカムとは関係なく、検疫についてはずっと]考えていました。

The reason Contagious Cities came about was because my background was history and philosophy of science and I had already been interested in quarantine and a history of quarantine. I’d been thinking about an exhibition of quarantine. It is ancient – crosses time – and global in a true sense. Everywhere in the world has had some experience of dealing with quarantine. And it’s also very poetic. It means the space of 40 days, from quarantina giorni in Italian. So I thought there is something poetic and something universal over time, that means it would be an interesting topic. So I’d been thinking about that anyway.

ウェルカムでは公衆とステークホルダーに向けた何か、と言われました。当時「感染症流行対策イノベーション連合」(CEPI)(*1)がちょうど設立されたところでした。それは、政府と企業とNGOが共同で感染症の流行に対する備えを考える試みです。私としては、感染症の流行対策については主題としてあまり考えたことがなかったのですが、CEPIが設立されたばかりで、これはステークホルダーにとっても面白いテーマになるだろうと思えました。私にとって、公衆とかステークホルダーという語は大きすぎる表現なので、もっと絞り込んでいかなければなりません。具体的なところから、なぜこれが適切なのかを理解する必要があるのです。だからCEPIが発足したことと、具体的な都市が挙げられていること、そして自分自身が検疫に興味のあること、さらにスペイン風邪と呼ばれた1918年のパンデミックの100周年だったことも加えて、「Contagious Cities(伝染性の都市)」というテーマが相応しいとなりました。

And they said something about public-facing and stake-holder facing. CEPI (Coalition of Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) had been just set up at that time. It was a collaboration among governments, businesses and NGOs to think about epidemic preparedness. I’ve really not thought about epidemic preparedness as a thing. Because CEPI had just been set up, I thought this would be interesting to the stakeholders. To me, public and stakeholders are such big terms. Too big, so I have to narrow them down. I have to get to be specific to understand why something would be relevant to everybody. So CEPI had been set up, those were the cities given, I had an interest in quarantine, and it was the centenary of the Spanish flu as it was called, the last pandemic in 1918, so that also makes this topic of Contagious Cities relevant.

次に、どんなアーティストがこの機会に関心を持ってくれるかを考え始めました。それから、世界のどこで、これ[感染症や検疫]について考えている人がいるのかと。ジュネーブには「ショックルーム(SHOC room)」と呼ばれる場所があります(*2)。そこは日常的に世界中の感染症の監視を行なっている場所の一つです。国際的な専門家のチームが、送られてくるデータをもとに何が真実で何が流言なのかを決定しています。すごく面白いですよね。一体どうやって[真実か嘘かを]決めるのか? アーティストインレジデンスのとても面白い場所になるだろうと思いました。

Then I thought which artists would be interested in these opportunities. Where in the world are people thinking about that? As in Geneva, there is a place called the “Shock Room” and it is one of the global observatories of infections on a daily basis. Quite an international team of people are looking at all the data coming in and they have to decide whether something is fact or rumor. That’s interesting. How do you decide? At the time, I thought that would be a really interesting place to have an artist in residency.

誰がレジデンスをできるのかを考えてみました。そこで仕事するには、高い適応力と柔軟性が必要です。そのためには、いろいろな人と話してみて、どんな意味のあるつながりをつくることができるのか考える必要がありますね。

I tried to think about who could be a resident there. You have to be quite adaptive and flexible, if you would like to work here, who, where and how? It just doesn’t emerge, you have to talk to people. Where can you make a meaningful connection, having a residency in a place of relevance to the topic.

WHO本部のSHOCではBlast Theoryがレジデンスを行い、インスタレーションとインターネット上のインタラクティヴな作品「A Cluster of 17 Cases」https://www.17cases.comを制作。Blast Theoryは英国ブライトンで1991年に結成されたMatt Adams、Ju Row Farr、Nick Tandavanitjによるアーティストのコレクティヴ。ポピュラーカルチャーや新しいテクノロジーを援用したパフォーマンスやゲーム、映像作品、アプリ、インスタレーションなどを手がける。

Contagious Citiesを通したいちばんの発見は何でしたか?たくさんあると思いますが、ひとつ例を挙げるとすると。

What was the most interesting discovery for you from Contagious Cities? I guess there are many, but if you could give me one example!

まず思いついたのは、危機的な時代における文化団体の役割についてです。[「Contagious Cities」では]香港のパートナーたちと仕事をしていて、彼らは難しい時期にそのことについて本当にたくさん考えていました(*3)。それは発見というのではないですが、私がそれまであまり考えたことのないことでした。

Immediately I thought about the role of cultural organizations in a time of crisis, because of working with partners in Hong Kong. They think about that a lot in their difficult times. It’s not a discovery but just kind of something I had not really thought about.

私は時間をかけてアート実践の価値を認めていくことに興味があります。「Contagious Cities」は[そのとき限りの]プロジェクトでしたが、関係性は続いています。一緒に働いたあらゆる人たちとの関係が続いているのです。なので時間をかけてわかっていけば良いと思っています。「Art in Global Health」で一緒に働いたアーティストとも関係性は続いているし、アーティストたちと時間をかけて仕事をできることに感謝しています。それはより哲学的なアプローチにもつながると思います。

I’m really interested in acknowledging the value of artistic practice over time. Contagious Cities was the project, but the relationships continue. We have continuous relationships with all the people we’re working with, which I hope will come to light later on. Even artists like Katie Paterson. I was working with her at Art in Global Health. I continue to have a relationship and interest in her work, so I appreciate working with artists over the longer term. Being in dialogue with artists allows a more philosophical approach, I guess.

次のプロジェクトであるMindscapesはニューヨークとベルリン、東京、ベンガルールで行われます。

Your next project Mindscapes is held in New York, Berlin, Tokyo and Bengaluru.

「Mindscapes」ではすでに強いつながりのあるニューヨークとベルリンで行うことにしました。では、まだあまり関係性のない場所はどうか、ということで、もっとつながりをつくっていきたい東京とインドが選ばれました。

In Mindscapes, we already have strong relationships with New York, so it makes sense to carry on with New York, And Berlin. We then thought “What about places where we don’t have many relationships?” We chose Tokyo and India because we would like to have more relationships with them.

インターナショナル・プログラムを行う上で最も大変なこととは何ですか?

What is the most challenging part of international programs so far?

面白いことに、あまり大変だと考えたことはないのです… でも現在、個人的に最も大変なことと言えば、すごく基本的なことですが、4人のチームが私1人になってしまったことです。現実的に、それは難しいものです。[インターナショナル・プログラムを]パンデミックの中で行うことは大変ですが、やりがいがあります。リモートワークについては複雑な心境です。というのも[リモートで]私たちはたくさん成し遂げてもきたからです。リモートワークのいいところもあります。でも、実際に人と会う方がはるかに良いと思います。アイヴィ・チェンの[Mindscapesのために描いた]イラストが時差について触れている点が大好きです。

It’s funny that I don’t ever think things are challenging… Well, the most challenging thing right now, personally, is very basic. It was supposed to be 4 people working on Mindscapes and now it’s just me. Very practically. That is hard. It’s challenging doing this in a pandemic, but also rewarding. I have mixed feelings about the way we work remotely. Because in some ways we’ve done a lot, I think. But I think just to meet in person is much better. I love the way Ivyy Chen’s illustration talks about the time difference.

わかります。時差はスクリーンから感じるリアルな要素のひとつですね。

I know. It’s one of the things I feel reality from the screen.

Courtesy of Ivvy Chen and Wellcome Trust

なぜ人類学の研究者?

Why Anthropologists?

それでは最後の質問です。Mindscapesのキュレトリアル・リサーチ・フェロー4人中3人が社会/文化人類学の専門家というのは偶然ですか?(*4)

This is the last question. Is it a coincidence that three out of four Curatorial Research Fellows for Mindscapes are specialized in social/cultural anthropology?

そうですね、全くの偶然です(笑)。違いを尊重することとか、他者への本質的な関心についての何かが原因かもしれません。人類学は複雑な歴史をもつ学問だと思いますが、コアはとてもオプティミスティックなものだと感じています。それに、人類学は特殊性や現実に根ざしています。またインゴルドに戻ってきますね。何が現実で、何が本物で、何が真実で、何が信じられるものなのか。そして誰が関係性を維持するのか。こういった問いは人類学における主要な関心ですよね? お互いを思いやらなければならないし、ときにはパワーバランスにも気をかけなければならない。そこに相互性があり、生に関する共通する関心があれば、とてもすばらしいことだと思います。人類学は本来的に協働的なものでしょう? ひとりでできないし、その場所に行かなければならない。

Ha ha ha, well, that’s totally a coincidence. Maybe because it’s something about respect for difference, or innate curiosity about others. I know anthropology has complicated histories, but I feel like at the heart it is very optimistic and…And it is grounded in specificity, grounded in the real, which comes back to Tim Ingold, again. What’s real, what’s genuine, what’s authentic, what can be trusted, who’s taking care of the relationships? It’s central to anthropology, isn’t it? You have to take care of each other and sometimes the power balance, but actually if it’s done well, really thoughtfully and considerately, as long as there’s mutuality to it, shared interest in life, I guess. I think anthropology is inherently collaborative, isn’t it? You cannot do it on your own. You have to be in there.

とても大切な点です。人類学の本質をそんなふうに理解してもらえることは珍しいかもしれません。でも、偶然なんですね

I think those are very important points. It’s not always happening as the way you recognize the essence of anthropology. But it’s a coincidence.

そうですね。素晴らしい偶然でした。

Yes, that’s a wonderful coincidence.

(2022/02/21オンラインにて、聞き手:登久希子)

キュレーター、カルチュラル・プロデューサー。現在、ウェルカムトラストでカルチュラル・パートナーシップス・リードを務める。科学の歴史と哲学、現代美術、ミュージアム、映画、ラジオが専門。ベルリン、ジュネーブ、ニューヨーク、香港で開催された「Contagious Cities」(2017-2020)、ナショナルトラストにおける「Relevance in Heritage Context」(2017)、ロンドンの科学ミュージアムにおける「Wonder Materials」(2015-2016)、ウェルカム・コレクションにおける「An Idiosyncratic A to Z of the Human Condition」(2014)など、イギリス国内外で数多くの展覧会やプロジェクトを企画してきた。

Danielle Olsen is a curator and cultural producer now working at Wellcome Trust as Cultural Partnerships Lead. She has a background in history and philosophy of science, contemporary art, museums, films and radio. She has curated many shows internationally, such as “Contagious Cities” (in Berlin, Geneva, New York and Hong Kong, 2017-2020), “Relevance in Heritage Context” (National Trust, London, 2017), “Wonder Materials” (Science Museum Group, London, 2015-2016), “An Idiosyncratic A to Z of the Human Condition” (Wellcome Collection, London, 2014), to name a few.